|

see bottom of page for complete discography

The grandchild of Jewish-Russian immigrants, Dylan

was born Robert Allen Zimmerman, on May 24, 1941, in Duluth, Minnesota, to Abe, who worked for the Standard Oil Company, and

Beatty Zimmerman. In 1947, the Zimmerman family moved to the small town of Hibbing, where an unexceptional childhood did little

to hint at the genious to come. Young Bobby started writing poems around the age of ten (including one called “For Mother” a poem he wrote for Beatty on Mother’s Day), and taught himself basic piano

and guitar in his early teens. Falling under the spell of Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and other early rock stars, he started

forming his own bands, including the Golden Chords and Elston Gunn (a variation on the name Elvis) and His Rock Boppers. According

to the 1959 Hibbing high school yearbook, his goal was "to join Little Richard." Even his hair style was fashioned after Little

Richard’s.

The young Zimmerman soon left Hibbing and started at the University

of Minnesota in the fall of 1959. The sights and sounds of the big city opened new opportunities for him, and he began to

trace contemporary rock and roll back to its roots, listening to the work of country, rock, and folk pioneers like Hank Williams,

Robert Johnson, and Woody Guthrie. At nights during the summer, he would try to pick up old blues stations from the south

that would play his favorite artists. Indeed, his interest in music had become so intense that he rarely found the time to

go to class. He began to perform solo at local nightspots like the Ten O'Clock Scholar cafe and St. Paul's Purple Onion Pizza

Parlor, honing his guitar and harmonica work and developing the expressive nasal voice that would become the nucleus of his

trademark sound. It was around this time, too, that he adopted the stage name Bob Dylan. At first he spelled it like Dillon,

after Matt Dillon from Gunsmoke. But he changed it to Dylan “because it looked better”. Some say he changed

to Dylan in honor of the late Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, though this is an origin he has continued to deny throughout his career.

Recorded in early 1961 at Bonnie Beecher's apartment

in Minneapolis:

Poor Lazarus { RealAudio }

Dink's Song { RealAudio }

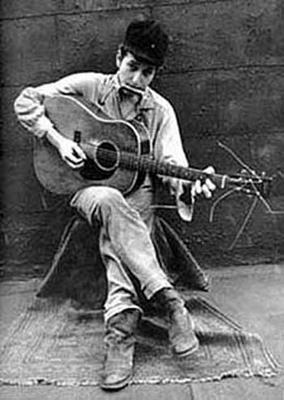

The following year, he dropped out of college and went to New York with two things on his mind: to become a part of

Greenwich Village's burgeoning folk-music scene, and to meet Guthrie, who was hospitalized in New Jersey with a rare, hereditary

disease of the nervous system (Huntington’s chorea). He succeeded on both counts, becoming a fixture in the Village's

folk clubs and coffee houses and at Guthrie's hospital bedside, where he would perform the folk legend's own songs for an

audience of one. Spending all of his spare time in the company of other musicians, Dylan amazed them with his ability to learn

songs perfectly after hearing them only once. He also began writing songs at a remarkable pace, including a tribute to his

hero entitled "Song to Woody."

In the fall of 1961, Dylan's legend began to spread beyond folk circles and into the world at large after critic Robert

Shelton saw him perform at Gerde's Folk City and raved in the New York Times that he was "bursting at the seams with talent."

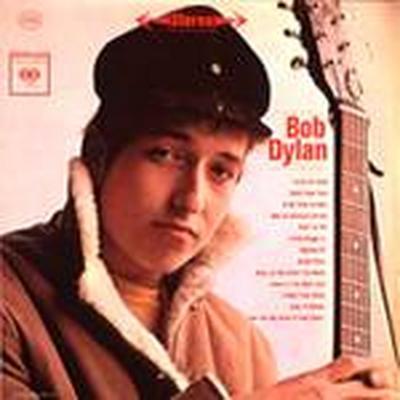

A month later, Columbia Records executive John Hammond signed Dylan to a recording contract, and the young singer-songwriter

began selecting material for his eponymous debut album. Not yet fully confident in his own songwriting abilities, he cut only

two original numbers, rounding out the collection with traditional folk tunes and songs by blues singers like Blind Lemon

Jefferson and Bukka White. The result (released early in 1962) was an often haunting, death-obsessed record that, culminating

in Dylan's gravel-voiced reading of "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean," sounded as much like the work of an aging black blues

man as a twenty-one-year-old Jewish folksinger from Minnesota.

Promising as that first album was, it didn't prepare anyone for the masterpiece that came next. The Freewheelin' Bob

Dylan, released in 1963, contained two of the sixties' most durable folk anthems, "Blowin' in the Wind" and "A Hard Rain's

A-Gonna Fall," the breathtaking ballads "Girl From the North Country" and "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right," and nine other

originals that marked the emergence of the most distinctive and poetic voice in the history of American popular music. Cementing

his reputation was Peter, Paul, and Mary's folksy cover of "Blowin' in the Wind," which went to No. 2 on the pop singles chart.

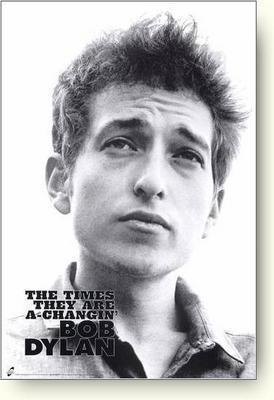

Dylan's next album, The Times They Are A-Changin', provided more of the same: the title cut and "The Lonesome Death

of Hattie Carroll" were the standout protest songs, while "Boots of Spanish Leather" was his saddest and most graceful love

song so far. At the same time, Dylan seemed to be tiring of his position at the forefront of the protest movement: in "Restless

Farewell," the record's last song, he concluded that he'd "bid farewell and not give a damn." Sure enough, his next album,

pointedly titled Another Side of Bob Dylan, was his most introspective and least topical to date, and its finale, "It Ain't

Me Babe," was an even more explicit goodbye to the folk movement he had helped reinvigorate.

The most revealing song on Another Side was "Ballad in Plain D," which painted a harsh, one-sided, blow-by-blow picture

of Dylan's breakup with his longtime girlfriend Suze Rotolo, who can be seen on his arm in happier days on the Freewheelin'

album cover. (More than twenty years later, Dylan said this was the one song in his catalogue that he wished he hadn't released.)

Shortly after his split with Rotolo, he became involved with the world's most famous folk diva, Joan Baez. The relationship

proved beneficial for them both, as Baez raided Dylan's unreleased material for her albums and introduced him to thousands

of fans at her concerts.

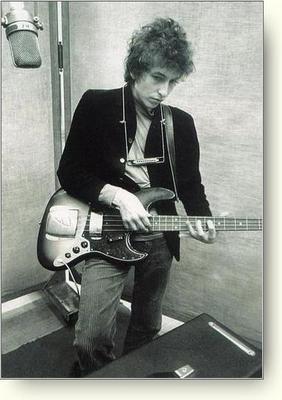

At the

same time, Dylan was itching to move beyond the acoustic musical constraints the folk movement imposed. Early in 1965, he

went into the studio with a nine piece band and recorded Bringing It All Back Home, a half-electric, half-acoustic album of

complex, incisive, biting songs like "Subterranean Homesick Blues" (featuring the trademark line, "You don't need a weatherman

to know which way the wind blows"), "Mr. Tambourine Man," and "It's All Over Now, Baby Blue." A week after Dylan cut Bringing

It All Back Home, the Byrds electrified his acoustic "Tambourine Man," and by the time it reached the top of the charts the

term "folk-rock" had become part of the contemporary lexicon.

Dylan's own transition from folk troubadour to rock bard was not quite so smooth: debuting his new material with the

Paul Butterfield Blues Band at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, he was famously booed off the stage. Such resistance notwithstanding,

Dylan's fame had long since eclipsed Baez's, and their relationship was starting to crumble. (D.A. Pennebaker's documentary

Don't Look Back was filmed during this period, and it clearly shows the tension between Dylan and Baez.) He had begun to see

Sara Lowndes, a friend of his manager Albert Grossman's wife, and by the end of the year would marry her. In the meantime,

he recorded and released the album Highway 61 Revisited, which contained the monumental single "Like a Rolling Stone." Clocking

in at more than six minutes, it was the longest, angriest (according to Rolling Stone magazine) song ever released on a 45,

and it reached No. 2 on the Billboard singles chart.

Next up was Blonde on Blonde, a two-record set recorded in Nashville in early 1966, which took the stream-of-consciousness

lyrics and edgy rock sounds of Highway 61 Revisited to the next level of artistry. From the raucous party rock of "Rainy Day

Women #12 & 35" to the rambling, hallucinogenic folk 'n' blues of "Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again"

to the poignant, apocalyptic balladry of "Visions of Johanna" and "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands," Blonde on Blonde took rock

and roll to places no one else had even dreamed of. A tour of England with the Hawks (who would later change their name to

the Band) produced music that was even wilder and more astonishing, though many of Dylan's old fans continued to be baffled.

The tour reached its peak at the Manchester Free Trade Hall on May 17, 1966, when the combo recorded a live set that was bootlegged--and

mis-titled--as Live at the Royal Albert Hall. (If you're lucky enough to find the two-CD bootleg Guitars Kissing & the

Contemporary Fix-- which features a pristine recording of the entire show--buy it; it's

the greatest album never released.)

By this time, Dylan was routinely being hailed

as the most important voice of his generation, but he was reaching a breaking point; he was, after all, only twenty-five years

old. He was battling heroin addiction and suffering from the constant touring. "The pressures were unbelievable," he would

later tell biographer Anthony Scaduto. "They were just something you can't imagine unless you go through them yourself. Man,

they hurt so much." A near-fatal motorcycle accident on July 29, 1966, proved a blessing in disguise, allowing Dylan to retreat

to the solitude of his home in Woodstock, New York, with Sara and their newborn son Jesse to reevaluate his career and priorities.

(The Dylan’s would ultimately have four children, with Bob adopting Sara's daughter from a previous marriage Maria,

then Jesse, Anna, Sam and then Jakob in 1969)

A

few months later, the Hawks joined him at Woodstock, and they began recording the loose, country-flavored tracks that would

be bootlegged (and released eight years later) as The Basement Tapes. Dylan's next official release, though, was the even

more low-key John Wesley Harding. Recorded in Nashville with a three-piece backing band, John Wesley Harding was widely considered

to be Dylan's pointed reaction to the Beatles' musically and technically complex landmark LP Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club

Band--an interpretation he naturally denied.

While John Wesley Harding earned glowing reviews and reached the No. 2 spot on Billboard's album chart (making it his

most commercially successful album to date), it also painted Dylan into an artistic corner. Gone was what he called his "thin

wild mercury sound," and gone were his outlandish, visionary lyrical flourishes; the simple, often elegant

songs that he was now writing could not support the hype that painted Dylan as one of the twentieth century's great poets.

Nashville Skyline, his next album, seemed to revel in disappointing fans' expectations: it was a straight country record,

and despite some lovely songs (especially "I Threw It All Away") and a hit single ("Lay Lady Lay") it was seen as Dylan's

first real artistic misstep.

As it turned out, Nashville Skyline was just

the beginning of Dylan's slide in the eyes of the critical establishment. Self Portrait, the two-record set which followed

in 1970, was viewed as a genuine disaster: "What is this shit?" Greil Marcus asked in his Rolling Stone review. New Morning,

released four months later, was a comeback of sorts--it was at least listenable--but it was a far cry from Dylan's best work.

The release of his long-awaited book Tarantula in 1971 didn't do anything to rehabilitate his reputation in hip circles. Even

his inspiring set at the George Harrison-organized Concert for Bangladesh--Dylan's first American concert appearance since

his motorcycle accident five years earlier--seemed to hint at artistic confusion: he didn't perform a single song written

after 1966.

Seemingly floundering, Dylan accepted an invitation from legendary Western filmmaker Sam Peckinpah (The Wild Bunch)

to appear in and compose the score for his new film, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, which was filming in Mexico and would

star Dylan's friend Kris Kristofferson. The shoot was not a pleasant experience: the Mexican location proved difficult, Peckinpah

was preoccupied with studio politics (the film was eventually taken out of his hands and recut), and Dylan floundered in the

role of Billy's sidekick, Alias. But the soundtrack album was a success, and the single "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" broke

the Top 20 (and went on to become one of Dylan's most covered songs).

At this point, it had been seven years since Dylan's motorcycle accident, and he had not mounted a full-scale tour

since. In the summer and fall of 1973, he and the Band started rehearsing the Dylan songbook for a comeback tour, and in early

November they took a few days off to record the album Planet Waves. It was a hasty, underwritten effort, but that didn't stop

it from shooting to the top of the charts after Dylan and the Band hit the road for a nationwide tour in January of 1974.

(Planet Waves was, in fact, Dylan's first No. 1 album ever.) The concerts were the stuff of legend, and promoter Bill Graham

said that there were mail-order requests for more than twelve million tickets, though only 658,000 seats were available for

the forty shows. An acclaimed two-record live set, Before the Flood, came out within a few months of the tour, and made it

to No. 3 on the charts.

While the

tour seemed to reinvigorate Dylan's creative spirit, his personal life was in a shambles. He and Sara had separated, and Dylan's

confusion, pain, and anger over their split infused the songs he was writing with a rare passion. The result was Blood on

the Tracks, perhaps the most mature, moving, and profound examination of love and loss ever committed to record. Stunning

songs like "Tangled Up in Blue," "Idiot Wind," and "Shelter From the Storm" were not strictly autobiographical, but their

emotional turbulence clearly reflected Dylan's anguished state of mind. His second straight No. 1 album, Blood on the Tracks

didn't merely match the brilliance of Dylan's sixties output--in terms of eloquence and emotional authority, he had reached

new heights.

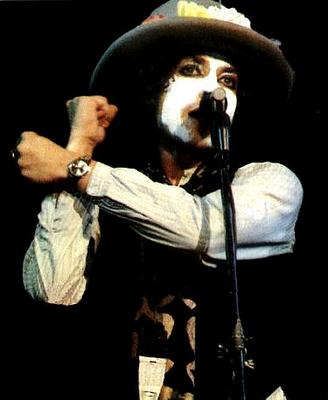

Later that year, a truncated version

of The Basement Tapes was finally released, and was hailed as a found masterpiece. Another tour soon followed--the ragtag

Rolling Thunder Revue, which featured old friends like Joan Baez and Roger McGuinn, and new ones such as T-Bone Burnett and

playwright Sam Shepard, who was recruited to write a screenplay to be shot on the road. (The resulting film, the mostly unscripted

Renaldo and Clara, was a confused four-hour debacle that received very limited distribution in 1978.) Mid-tour, Dylan released

Desire, which was his third consecutive No. 1 album; it featured the single "Hurricane," dedicated to the wrongly imprisoned

boxer Rubin "Hurricane" Carter. While nowhere near as impressive as Blood on the Tracks, Desire was a well-crafted, evocative

effort that contained at least two great songs: the playfully cinematic "Black Diamond Bay," and the plaintive, heartfelt

ode to his estranged wife, "Sara." The song did not win her back: Dylan and Sara divorced the following year. He would later

marry (and quickly divorce) his backup singer Carolyn Dennis, with whom he had a child with, in 1982.

Dylan's first post-divorce album, Street Legal, did not bode well for the future. Overproduced and lyrically senseless,

it was even worse than Self Portrait, and the world tour that followed was a pale shadow of the Before the Flood and Rolling

Thunder shows. At thirty-seven, Dylan seemed, both personally and professionally, at loose ends. Even so, his next move took

the world by surprise: embracing fundamental Christianity, he released the overtly born-again album Slow Train Coming. Much

to the surprise of his critics, the record was a commercial success, reaching No. 3 on the charts, spawning the hit single

"Gotta Serve Somebody," and earning Dylan his first Grammy award, for Best Male Rock Vocal Performance.

The tour that followed was a fire and brimstone affair that managed to alienate many of Dylan's longtime fans, and

his next album, Saved, failed to crack the Top 20. For the faithful, though, his next record, Shot of Love offered signs of

hope: "Every Grain of Sand" was a gorgeous, philosophical ballad that took a far more forgiving tone than his past two albums,

while "The Groom's Still Waiting at the Alter" (the non-LP B-side to the single "Heart of Mine") was a barn-burning rocker

that would have fit nicely on Highway 61 Revisited.

Infidels (1983) continued the positive trend: co-produced by Dire Straits frontman

Mark Knopfler, whose graceful guitar work made it Dylan's best-sounding record ever, it was also his finest sustained collection

of songs since Blood on the Tracks. Veering away from the overtly religious material of his last three albums, Dylan recaptured

the complexity and emotional subtlety of his best work on songs like "Jokerman" and "Don't Fall Apart on Me Tonight." Empire

Burlesque, his self-produced follow-up to Infidels, was almost as good, ranging from the blistering soul of "Tight Connection

to My Heart" to the gentle acoustic ballad "Dark Eyes," with only a few missteps.

While Dylan had toured regularly since returning to the stage with the Band in 1974, beginning in the mid-eighties

he hit the road full-time, first with all-star cronies Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers and the Grateful Dead, then, starting

in 1988, with a small rock combo led by guitarist and Saturday Night Live musical director G.E. Smith. Shows on the so-called

Never Ending Tour were generally sloppy, and Dylan tended to mumble his songs and glower at his audiences, but he stuck with

it--nine years later, he's hardly spent a month off the road.The original work he's released over the last decade has continued

to contain flashes of genius, but only the Daniel Lanois-produced Oh Mercy worked to any sustained effect. Check out the wild,

twelve-minute Dylan-Sam Shepard road song "Brownsville Girl" (from 1987's Knocked Out Loaded) or the hallucinatory Oh Mercy

outtake "Series of Dreams" (from the revelatory, career-spanning three-CD set The Bootleg Series) to hear the best of the

latter-day Dylan. Then there are the two fast and funny Traveling Wilburys albums, which catch Dylan--along with superstar

friends George Harrison, Tom Petty, Jeff Lynne, and (on the first record) Roy Orbison--in an uncommonly lighthearted mood.

He followed up 1990's Under the Red Sky with two albums' worth of old folk and blues covers: 1992's Good As I Been to You

and 1993's World Gone Wrong. While both are largely satisfying efforts, they didn't win him many new fans.

Early in 1997, though, those who lived in hope of an artistically born-again Dylan

had cause for optimism: musician Jim Dickinson told a Memphis newspaper that he had played on some recent, Daniel Lanois-produced

Dylan sessions featuring new material Dylan had composed while stuck at home in Minnesota during a blizzard. According to

Dickinson, one cut was seventeen minutes long, and overall the material was "so good, I can't imagine he won't use it."

The seventeen-minute song turned out to be "Highlands," the

closing cut on the critically acclaimed Time Out of Mind, which was released in September and became Dylan's first gold record

of the decade. The success of the album was noteworthy, but 1997 will go down as the year that Dylan knocked on heaven's door,

literally: in May, on the eve of a European tour, he was hospitalized with histoplasmosis, a potentially fatal infection that

creates swelling in the sac surrounding the heart. He had been suffering from heart pains while attending his grand daughter’s

birthday party at his daughter Maria’s house, and she quickly drove him to the hospital. Luckily, the songwriter made

a rapid recovery, and was back on the road by August and continued to tour through the remainder of the year, including a

September date in Rome at the behest of Pope John Paul II. In early December, Dylan was one of five recipients of his country's

highest award for artistic excellence, the Kennedy Center Honors.

In June of 2004, Dylan recieved a honorary degree from Scotland's

oldest university, St. Andrews. (This is his second honorary degree, the first coming from Princeton University in 1970.)

On October 5, 2004, Bob Dylan's memoires, titled Chronicles

Volume 1 was released, and made it to the number three spot on the New York Times Best Seller List.

And on November 27, 2005, Bob Dylan was inducted into

the UK Music Hall of Fame.

|

| Receiving Kennedy Center Honor from Bill Clinton. |

|

|

| Dylan recieving honorary degree from St. Andrews. CLICK ON PHOTO. |

|